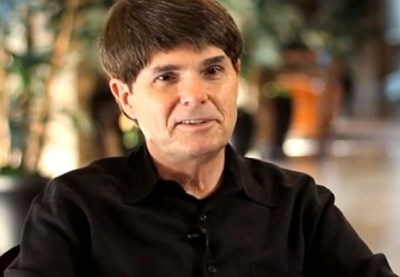

Talking with Dean Koontz

In 1988, when the first of his books was produced on audio, Dean Koontz was appalled. “I allowed an abridged version,” he says, “and the story became incoherent. I never realized that ‘abridged’ meant as much as 60 percent of the story would be cut!” The bestselling author bought back the audio rights to WATCHERS, the second book in the contract, and has insisted on unabridged recordings ever since.

As the years have passed and audio has become a much larger segment of the book market, maintaining the integrity of his work has become even more important to Koontz. “There’s a lot more money to be made in abridgments,” he notes, “but it’s not money worth having. You put too much effort into getting the story right in the first place to have it cut like that.” Audio versions of his work have definitely had an impact on listeners, which can be measured in the number of letters the author receives. For instance, when FROM THE CORNER OF HIS EYE was released in audio in 2000, his mail doubled.

While recognizing the importance of audio in the publishing field, Koontz doesn’t concentrate on the medium while writing, at least not in any obvious way. “I do always think about the music of language,” he says. “It can be a useful tool to put prose into subtle meter, and carry the reader along a passage without the reader entirely knowing how or why the words are having a certain effect.” But, he says, “I never start a book thinking about the movie; in fact, I hope a movie won’t be made. And I don’t think about the eventual audio production at all.” Koontz rarely reads his work out loud as he writes. “I’m embarrassed that someone will hear me,” he says. “I talk to myself too much anyway.” Although he’s getting a little more used to the idea—after all, he does sometimes laugh when writing a funny passage, or cry over the sad parts, so maybe an occasional reading out loud isn’t so bad, as long as no one but the dog is listening.

Koontz finds listening to audiobooks a very different experience than reading print, through which reader and author have a “direct” link with each other. In print, he says, the reader mentally “hears” his own interpretation of the work. In audio, a third person, the narrator, enters the mix, making the experience more passive, like watching a movie. “However, if the narrator is good, he can bring the listener and author securely together. A good performer, who can carry the story properly, can be a real benefit.”

Koontz trusts his producers to choose the best narrator for each book and has been satisfied with their choices. “I’ve heard some wonderful compliments about specific readers, especially for Kate Burton’s performance of INTENSITY and no great complaints about any of them,” he says. Beyond giving the producer a list of requested pronunciations at the start of a recording, the author doesn’t participate in the audio production. And he doesn’t listen to more than a few minutes of the finished product—“Too awkward. I don’t like to listen to my own stuff.”—Ruth P. Ludwig

FEB/MAR02

Photo © Jerry Bauer