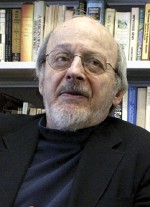

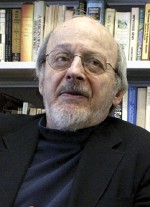

Talking with E.L. Doctorow

THE MARCH opens with the advance of Sherman’s army on a Georgia plantation. It is “a creature of a hundred thousand feet,” a “rhythmic tromp,” a “symphonious clamor,” but to the band of slaves waiting outside the plantation house it is the sound of freedom. Like all E.L. Doctorow’s novels, THE MARCH is rich in language, characters, and story lines, and is a feast for the eyes, ears, and imagination. On the eve of the publication of his tenth novel and the unabridged audiobook, narrated by Joe Morton, Doctorow talks about the ways his new work evokes the voices of the Civil War and nineteenth-century literature.

Q: Reading this book is like being along on Sherman’s march--and relieved not to be. How did you achieve such realism and period atmosphere?

A: That question is difficult for me because writing is largely a matter of feel, of intuition, of imaginative discovery. Something gets put down on paper almost before I know what it is. Then I see if it’s right. I can go as much by the tone of a word or a sentence as by the actual literal meaning.

Q: Your early novel RAGTIME and your recent collection SWEET LAND STORIES seem to breathe the unique tone and idiom of an era. Is this an effect you work to achieve, or is it incidental to other aspects of your historical research?

A: You work to achieve every effect on the page, but it’s not always an operation of the intellect. I’m responsive to the music in words, the rhythm of sentences. I come from a musical family though I’m not a musician myself, and I think that when I was a child, somehow the difference between notes on a staff and words on a page must have elided in my mind. So the writer’s mind is, among other things, a library of sounds, of dictions.

But the research is, of course, instructive. The reading I did for this book went on for several years, and much of it before I ever thought of Sherman’s campaign as the armature for a novel. Sherman’s own war memoirs are remarkable, almost at the level of Grant’s. They were both exceptional writers. And the thing you realize as you read them is how current their language is, how contemporary. In addition, there are documentary histories of the war, including accounts of people who were on the march or witness to it, and it is almost shocking, if not heartbreaking, to realize how little life changes, and how recognizable the thoughts and feelings of that time were, so that really the only difference between now and then is the furniture of our lives, the technology. So you could say that writing about the past is partly a matter of furnishing the present appropriately.

Q: You read frequently in public, and narrated the unabridged audiobook of RAGTIME. What qualities do you work for as a performer of your own fiction?

A: When I read in public, it is not ordinary reading, but it is not acting either; it is something in between. It has the vitality of performance but is in service to the words. The listener should hear the book talking, not the reader. That is why so many actors make bad readers; they don’t find that middle ground. Joe Morton was my choice for THE MARCH. I had listened to his other work. He gets it; he knows the art.

Q: Gets the character voices, of which there are so many--

A: Yes, lots of voices in THE MARCH. This is a heavily populated novel.

Q: Gets the character voices, and also something in the tone of the book, that “sound of expectation” the plantation slaves hear at the beginning of the book, as Sherman’s army advances--

A: Yes, not only people talking, people thinking. Men, women, black, white, generals, foot soldiers, refugees. But the book talks and thinks; the narration is omniscient. What I believe Morton accomplishes is what I wanted from the text. I wanted the book to march. I wanted that narrative advance, and he renders it. There have been several audio recordings of my books. This may be the best of them.

Q: You are an admirer of Melville, and in many ways your narrative style has closer affinities to the great nineteenth-century voices like Melville and Irving and Twain, rather than to our pared-down style today.

A: You don’t think about these things as you’re working. But it is true that somewhere along the middle of the book I began to feel I was writing a novel as novels used to be written. Lots of characters, extensive terrain. And in the third person. Sort of a nineteenth-century Russian novel is what I felt I was doing, though there are no Russians in it.--David Walton

DEC 05/ JAN 06

© AudioFile 2005, Portland, Maine

Photo © AP/Wide World Photos/Mary Altaffer